Muž se železnou láskou

| 31. 1. 2022„Nebude vadit, když o železe budu mluvit anglicky? Nejsem zvyklý o něm přemýšlet v češtině,“ říká v úvodu našeho setkání Tomáš Ganz, objevitel klíčových hormonů regulujících metabolismus železa, který už šestapadesát let působí ve Spojených státech. Do angličtiny ale přejde i po otázce na vztah k Praze. Protože i to je věda… Příběh jeho rodiny je mimo jiné výpovědí o pohnutých dějinách střední Evropy 20. století.

English version below

Váš otec Vilém Ganz byl úspěšný kardiolog, později už jako William dokonce světoznámý, takže k vědě jste měl blízko od dětství. Ale stačilo málo a vše mohlo být dramaticky jinak. — To je pravda. Táta se narodil v Košicích, v roce 1937 začal studovat medicínu v Praze. Ale po Mnichovu připadly Košice Maďarsku, táta přišel o české občanství, z univerzity ho vyhodili a on se vrátil domů. Jako Žid se ocitl v maďarském pracovním táboře. Do opravdového nebezpečí se dostal, když v roce 1944 přišli Němci a začaly transporty.

Co ho zachránilo? — Spíše kdo ho zachránil. Přišel za ním maďarský voják a povídá: „Němci tě zlikvidují. Neposlouchej, co ti říkají. Tady máš lístek na vlak do Budapešti, tam je to bezpečnější. Moje služka tě vezme na nádraží.“ A tak se stalo. Táta ho dobře neznal a nevěděl, proč to udělal. Hrozil mu za to trest smrti, i celé rodině. O více než padesát let později jsem byl na kongresu v Miláně a tam mě oslovil člověk zhruba mého věku: „Jmenuji se Oliver Rácz, jsem patolog z Košic a jsem syn toho muže, který zachránil vašeho otce.“

Tomu říkám setkání! — Bylo to neuvěřitelné. Znal celý ten příběh. Jeho otec, Oliver Rácz starší, už byl v té době po smrti, zemřel v roce 1997.

Dozvěděl jste se, proč vašemu otci tehdy pomohl? Pomáhal i dalším lidem? — On měl takovou disidentskou povahu. Byl levicového smýšlení, v šedesátých letech byl za komunisty poslancem Slovenské národní rady a potom i Sněmovny národů Federálního shromáždění (do r. 1971, pozn. red.), ale nebyl nijak kovaný. A za války měl dívku, Židovku – později se vzali. Pomohl nejprve jí a potom i dalším lidem, otec nebyl jediný.1) Tak myslím, že v tom hrály roli dva faktory: láska a idealismus. Později jsem pomohl dostat jeho jméno do památníku Jad vašem.

Otec tedy válku přežil, jaké byly jeho další osudy? — V Budapešti potkal mámu, která byla také v podzemí. Po válce se vzali a táta se vrátil k studiu medicíny na Karlově univerzitě. Promoval v roce 1947. Myslím, že byl rok v pohraničí, pak nastoupil do Nemocnice Na Bulovce, kde mu šéfoval profesor Klement Weber. Ten se v roce 1951 stal ředitelem nově založeného Ústavu pro choroby oběhu krevního v Krči. Věděl, že má táta talent, tak ho tam pozval. Táta se v ústavu věnoval výzkumu, jeho specializací byl koronární oběh. Dělal skutečně špičkovou vědu na mezinárodní úrovni, publikoval ve světových časopisech, takových odborníků u nás tehdy mnoho nebylo.

Vy jste se tedy narodil v Praze. — Na klinice v Rooseveltově ulici. Máma později říkala, že jméno té ulice předurčilo můj osud.

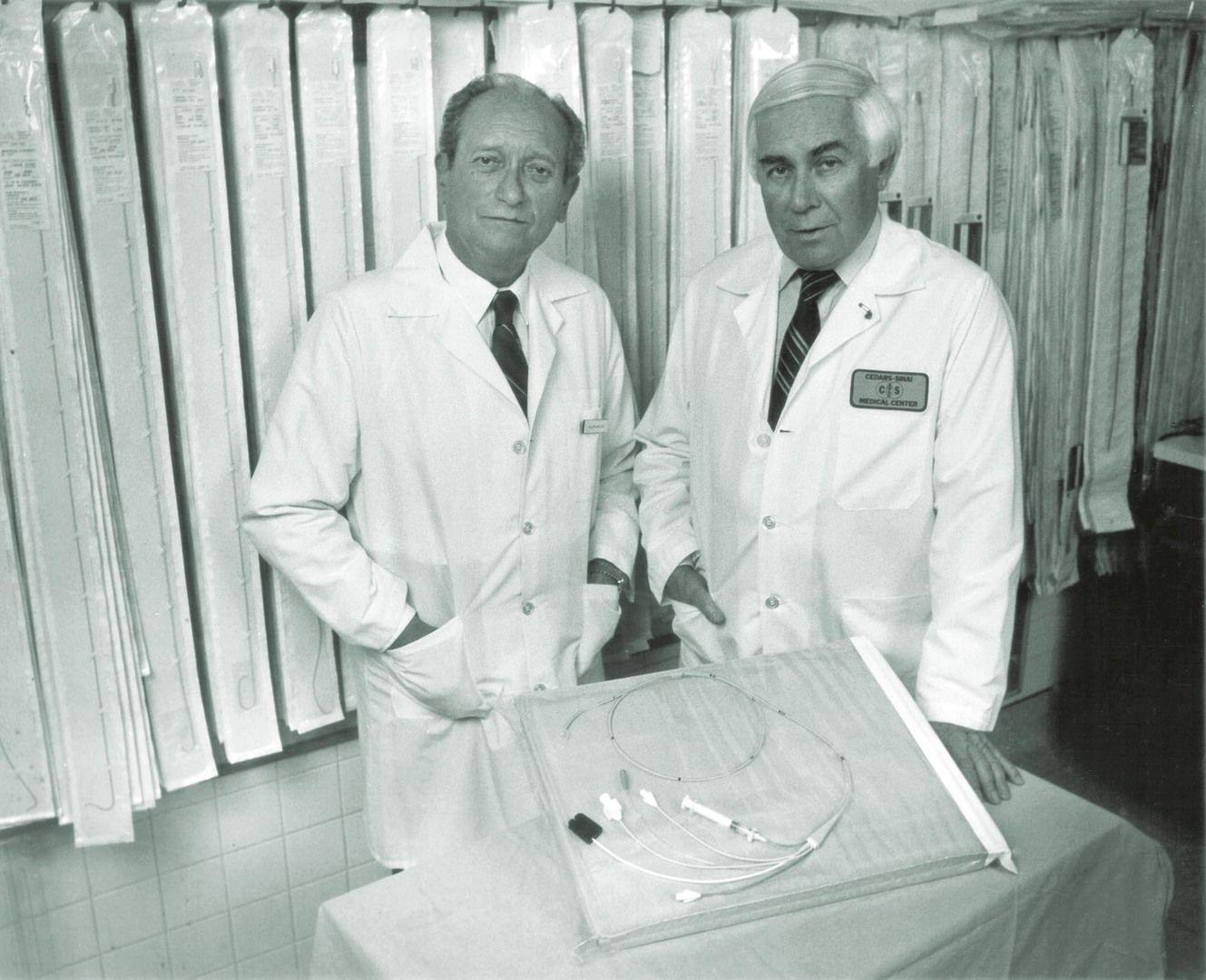

Osud emigranta do Spojených států? — Odešli jsme celá rodina v roce 1966, to mi bylo osmnáct. Nevím přesně, jak se to tehdy podařilo, ale dostali jsme všichni pasy a jeli jsme na dovolenou do Rakouska a Itálie. A nevrátili jsme se. Máma měla bratra a sestru v Los Angeles, takže jsme šli za nimi. Táta se naučil anglicky, získal pozici v Cedars-Sinai Medical Center a pokračoval ve výzkumu, který začal v Krči.

A úspěšně. — Úspěšně, v koronární fyziologii byl velice úspěšný. Byl to nejen vědec, ale i vynálezce. Pracoval rukama, počátkem sedmdesátých let s Jeremy Swanem vyvinuli tzv. Swanův-Ganzův katétr pro měření krevního tlaku a průtoku v plicnici. To je zvláštnost a přednost Ameriky. Člověk tam může přijít, nemá dobrou angličtinu, nezná tamní systém, a přesto se může prosadit.

Váš mladší bratr šel v otcových stopách. — Ano, bratr Peter je úspěšný kardiolog na Kalifornské univerzitě v San Francisku. On na to měl odvahu, já chtěl dělat něco jiného.

Dokonce něco úplně jiného. Nebyla to hned hematologie, že? — Kdepak, dělal jsem fyziku. V Praze jsem chodil na gymnázium ve Štěpánské ulici, byl jsem takzvaný kyberneťák. To byl tehdy takový experimentální program, měli jsme každý týden pět hodin fyziky a deset hodin matematiky. A také programování. Líbilo se mi to, měl jsem nastoupit na Matfyz. Když jsem pak začal studovat na Kalifornské univerzitě v Los Angeles, zařadili mě rovnou do druhého ročníku, protože jsem měl z gymnázia před americkými studenty rok náskok. Na doktorát jsem potom šel na Caltech, kde jsem pracoval na supravodivých obvodech. Šlo mi to, bavilo mě to, tak mě ani moc nezajímalo, kdo výzkum financuje. Ale byla to armáda. A když skončila vietnamská válka, byl výzkum, na kterém jsem pracoval, mezi prvními, jejichž financování se zastavilo. Tak jsem si řekl, že musím zkusit něco jiného.

Jak se stane, že se fyzik obrátí k medicíně? — Zajímala mě biologie, i když jsem se ji nikdy předtím neučil. Měl jsem profesora, který mě v tomto směru inspiroval – Maxe Delbrücka.

Vás učil Max Delbrück? — Ano, nositel Nobelovy ceny za rok 1969. Byl to fyzik, který se prosadil v biologii a mě k ní přivedl. Zabýval se genetikou a viry, chtěl jsem dělat to co on. To se tak docela nevydařilo, protože jsem zjistil, že se vše musím naučit sám. S jedním doktorátem nešlo usilovat o další – jedinou výjimkou byla medicína. Tak jsem kvůli biologii šel studovat medicínu. Ne že by mě nezajímali pacienti, ale chtěl jsem být především vědec – jako táta a jako moji hrdinové, o kterých jsem četl ve Vesmíru a v Scientific American.

Co rozhodlo o vaší další specializaci? — Nechtěl jsem dělat na populárních tématech, ve kterých je velká konkurence a obrovský tlak na výsledky. Chtěl jsem mít čas vše pořádně promýšlet. Nelákal mě proto výzkum rakoviny a podobné atraktivní věci. Hledal jsem obor, v němž bude „ticho a klid“. Měl jsem štěstí, že jsem se jako postdok v roce 1983 dostal k Robertu Lehrerovi, který mě přivedl k hematologii. Přišla mi hrozně zajímavá – i proto, že můžete snadno získat vzorky pro výzkum.

Totéž mi říkal Josef Prchal: „Odebrat krev si většina lidí nechá celkem ochotně. Udělat biopsii mozku nebo srdce je o poznání komplikovanější.“ (Vesmír 100, 668, 2021/11) — Je to tak. Na krev se hned můžete podívat pod mikroskopem, je ještě živá, buňky se hýbou… Fantastické!

Ale nemrzelo vás, že jste opustil fyziku? — Trochu ano, ale občas se mi její znalost hodila. Uměl jsem například opravit laboratorní přístroje. Ušetřil jsem tím tisíce dolarů.

A šlo jen o tuto praktickou výhodu? Fyzikové přece jen přemýšlejí jinak než biologové, Max Delbrück nebyl jediný, kdo biologii obohatil fyzikálním přístupem. — To máte pravdu. Fyzika mi dala dvě věci: kvantitativní myšlení a schopnost dělat odhady. Neptat se jen, co se stane, ale kolik se toho stane. Pokud použiju tenhle přístroj, změřím nebo uvidím to, co změřit nebo vidět potřebuju? Je ten přístroj dost citlivý? Mnozí biologové nejsou zvyklí takto přemýšlet.

Lehrer vás přivedl ke studiu antimikrobiálních peptidů? — Ano, on byl v této oblasti průkopníkem. Položili jsme si otázku, zda bílé krvinky tvoří antibiotické substance, které organismu pomáhají bojovat s bakteriálními infekcemi. V té době panovalo všeobecně přijímané přesvědčení, že bílé krvinky zabíjejí patogeny tím, že tvoří kyslíkové radikály. Ale my jsme měli pacienty, kteří žádné kyslíkové radikály netvořili, a přesto se nenakazili. Ptali jsme se, zda neexistují ještě nějaké jiné způsoby likvidace mikrobů. Náš přístup ke studiu tohoto problému byl velmi jednoduchý, ale fungoval: Sbírali jsme miliardy bílých krvinek od lidí i zvířat a pak jsme vzali extrakt, dali ho bakteriím a pozorovali jsme, které extrakty je dovedou zabíjet. Tak jsme objevili peptidy s antimikrobiálními účinky, které jsme pojmenovali defensiny. Zkoumal jsem je potom deset let. Přišli jsme na to, že defensiny nejsou jen v bílých krvinkách, ale také v kůži, na sliznicích, v moči… Našli jsme je prakticky všude.

A takhle jste objevil hepcidin… — Jednoho dne mi laborantka přinesla ukázat chromatogram. Byl to vzorek z lidské moči. Podíval jsem se na něj a bylo mi jasné, že tam je něco neznámého. Ten peak nereagoval s našimi protilátkami proti defensinům. Analyzovali jsme ho a byl to nový peptid. Stejně jako defensiny dokázal zabíjet bakterie a zjistili jsme, že pochází z jater. Proto jsem ho pojmenoval hepcidin.2)

Jak jste přišli na jeho roli v regulaci železa? — Nový peptid jsem vložil do databáze a vzápětí se mi ozval kolega z Francie. Že našli ten samý peptid v myších, kterým dávali potravu bohatou na železo.3) Zjistili, že játra těch myší tvoří velké množství tohoto peptidu. To se mi v hlavě rozezněl zvonek: Tohle nebude normální defensin! Jeden z lidí, kteří pracovali v té francouzské laboratoři, pak přešel do jiné laboratoře, v níž měli transgenní myš s knokautovaným genem pro USF2 (jeden z transkripčních faktorů, pozn. red.). Když ji otevřeli, zjistili, že má játra a slinivku úplně tmavé od železa, a naopak má v porovnání s kontrolou méně železa ve slezině. A vše si to spojili: Geny pro hepcidin a pro USF2 jsou hned vedle sebe a ukázalo se, že v myši byl knokautovaný i gen pro hepcidin.4) Takže je napadlo, že by hepcidin mohl být hormon regulující železo, který všichni hledali. Ptali se nás, co si o tom myslíme. No a já jsem zahodil vše, na čem jsem v té době pracoval, a začal jsem se plně věnovat hepcidinu. Díky myším modelům i lidským pacientům jsme to postupně dali dohromady: hepcidin je hormon regulující množství železa v organismu.

„Z vlastní moči jsem získal několik miligramů hepcidinu. Byl to tak bohatý zdroj! V angličtině máme rčení: když ti bůh dá citrony, udělej citronádu. Tak já jsem udělal hepcidin.“

Hepcidin reguluje železo podobně, jako inzulin reguluje cukr? — Je to přesně to samé. Oba jsou to peptidové hormony, inzulin snižuje hladinu krevního cukru, hepcidin snižuje hladinu železa. Je ale zajímavé, že vzniká v játrech. Nejsme zvyklí o nich přemýšlet jako o endokrinní žláze, ale je to tak. Pokud se hepcidin netvoří, ať už kvůli mutacím v regulačních genech a oblastech, nebo v samotném genu, člověk onemocní hereditární hemochromatózou. Zdravý člověk má v těle tři nebo čtyři gramy železa. Lidé s nefunkčním hepcidinem ho mohou mít desetinásobek. Nadbytek železa pak bez léčby zničí v těle všechno – játra, slinivku, srdeční sval… A pokud se hepcidinu tvoří naopak příliš mnoho, člověk onemocní anemií z nedostatku železa – není ho dost pro tvorbu hemoglobinu.

Hepcidin se váže na feroportin – transmembránový protein v enterocytech (buňkách tvořících střevní výstelku) dvanáctníku, v makrofázích a v některých dalších typech buněk. Feroportin zajišťuje transport železa z buňky do krve. Hepcidin ho blokuje a způsobuje jeho degradaci. Pokud ale železo dál s potravou přichází, co se s ním děje? Hromadí se v enterocytech, nebo ho přestávají ze střeva vstřebávat? — Děje se obojí. Železo se kumuluje v enterocytech dvanáctníku, které ho v určitém okamžiku přestanou dále absorbovat. Ale nejdůležitější je, že enterocyty žijí jen dva až tři dny. Takže buňka odumře a my ji spláchneme do toalety – i s tím železem. Enterocyty jsou samy o sobě fascinující, mohli byste vyprávěním o nich zaplnit celý časopis. Proč vlastně tělo produkuje buňky, které žijí tak krátce? Vysvětlením může být korozivní prostředí, kterému čelí. Když teď v kavárně jím salát, může mě napadnout, jak to, že ho moje tělo stráví, ale střevní buňky přežijí? Správná odpověď je, že ty buňky zase tak dlouho nežijí. Umírají brzy, proto je tělo musí tak intenzivně obnovovat.

Jak je to vlastně s tou antimikrobiální aktivitou hepcidinu, kvůli které jste si ho poprvé všiml? — Myslím, že to je taková evoluční kuriozita. Funkce hepcidinu není primárně antimikrobiální, ale nese si s sebou svůj evoluční původ – patří pravděpodobně do stejné skupiny peptidů jako defensiny. Ale roli v obraně organismu hraje. Při infekci se hladina hepcidinu dramaticky zvýší – klidně tisíckrát. Když jsem trpěl infekcí močových cest, sledoval jsem sám na sobě hladinu hepcidinu. Stoupla na tisícinásobek a pak opět klesla. Z vlastní moči jsem získal několik miligramů hepcidinu. Byl to tak bohatý zdroj! V angličtině máme rčení: Když ti bůh dá citrony, udělej citronádu. Tak já jsem udělal hepcidin.

Ale proč hepcidin vyletí tak vzhůru? — Železo je mimo jiné i potrava pro bakterie. Takže při infekci dává smysl snížit množství dostupného železa a bakterie vyhladovět. Pro organismus to není sebevražedné chování, protože červené krvinky žijí čtyři měsíce. Takže pokud tělo na týden nebo dva jejich produkci zastaví, vůbec to nevadí. Organismus kalkuluje: teď potřebujeme bílé krvinky, ne červené.5) A mikrobi potřebují železo. Tak zastavíme produkci červených krvinek a snížíme hladinu železa. Hepcidin to celé koordinuje. Víme to, protože jsme vytvořili transgenní myš, která hepcidin nemá. Když ji infikujete gramnegativními bakteriemi, zemře během dvanácti hodin, přičemž kontrolní myši ani neonemocní.6) Byl to děsivý experiment. Volali nám ze zvěřince: „Všechny vaše myši jsou mrtvé! Nemůžete v tom pokračovat, je to proti pravidlům.“

Hladina hepcidinu bývá vysoká i u chronického zánětu, což může vést k anémii. Ta už ale organismus poškozuje. Proč tedy hladina hepcidinu neklesne? — Můžeme se ptát, zda je lidem trpícím chronickým zánětem taková anémie k něčemu dobrá. Moje jednoduchá odpověď je: evoluce se nestará o chronické nemoci. V minulosti platilo, že máte-li chronickou nemoc, jste mrtvý. Pokud se člověk dožil třiceti nebo pětatřiceti let, byl to dlouhý život. Anémie tak může být vedlejší důsledek snahy ochránit tělo před infekcí, nemá žádnou funkci.

Jak je vlastně hepcidin v živočišné říši rozšířený? — Známe ho u obratlovců. Poprvé se objevuje u ryb. A u nich je to zajímavé, protože některé z nich mají dva druhy hepcidinu. Jeden funguje jako hormon a druhý možná jako antimikrobiální peptid. Opět jsme u evoluční historie hepcidinu. U bezobratlých schází, i když mají feroportin. Ten je znám i u primitivních mnohobuněčných živočichů, jako je nezmar. Našli jsme teď i nějaké bakterie, ale ty ho mohly ukrást živočichům.

Takže u bezobratlých je feroportin regulován jinak? — Ano, ale zatím nevíme jak.

Hepcidinem ale vaše objevy hormonů regulujících železo neskončily. — Hepcidin byl první částí toho vědeckého příběhu. Druhou částí byla otázka, jak si červené krvinky zajišťují dostatek železa. Musí existovat nějaký regulační mechanismus, který prekurzorům červených krvinek umožňuje „říct si o železo“. Tak jsme hledali další hormon a v roce 2014 jsme ho našli – erytroferon.7) Hodně práce na tom udělal můj francouzský postdok Léon Kautz. Erytroferon inhibuje hepcidin, tím pádem může feroportin pouštět do těla víc železa. Pořád na tom pracujeme. Nedávno nám vyšel nový článek v časopise Blood. Připravili jsme myš, která produkuje příliš mnoho erytroferonu, a trpí proto nadbytkem železa.8)

Když jsem si o regulaci železa četl, narazil jsem na to, že člověk může trpět zároveň nadbytkem železa i anémií. Jak se něco takového přihodí? — Jednou z možností je vznik anémie v důsledku léčby hemochromatózy. Hemochromatóza se léčí pomocí velmi starobylé metody, která se používala k lecčemu, ale v tomto případě má opravdu smysl – lidově řečeno pouštěním žilou. Mililitr červených krvinek obsahuje miligram železa. Takže pokud má pacient nadbytečných 10 gramů železa, musíte mu postupně vzít 10 litrů červených krvinek, tedy 20 až 30 litrů krve. Během tohoto procesu můžete vyvolat anémii, protože se železo nemobilizuje dost rychle.

A další možná příčina? — Existují nemoci, které kombinují anémii s něčím, co vypadá jako hemochromatóza. Příkladem je talasémie. Prekurzory červených krvinek produkují příliš mnoho erytroferonu. Příčinou je skutečnost, že se prekurzory dělí, přitom produkují erytroferon, ale nediferencují se v červené krvinky. Pacienti mají kostní dřeň v každé kosti – v lebce, v prstech, které jsou kvůli tomu oteklé… Kosti jsou plné prekurzorů, které se marně pokoušejí tvořit červené krvinky.

Proč se jim to nedaří? — Je u nich z genetických příčin poškozena tvorba jednoho z globinových řetězců (alfa, nebo beta), takže nastává nerovnováha, netvoří se hemoglobin, nadbytečný globin se v buňce sráží a zabíjí ji. Na nedostatek červených krvinek reaguje erytropoetin, jehož koncentrace vystřelí vzhůru a stimuluje tvorbu dalších červených krvinek. Ty ale vznikat nemohou. A během toho začarovaného kruhu prekurzory stále produkují erytroferon, který inhibuje hepcidin. Takže celý systém se zblázní.

Očekáváte objev dalších regulačních molekul? — Je možné, že erytroferon není ve své roli jediný, vidíme i stopy něčeho dalšího, ale na tom pracovat nechci. Většinu efektu dělá právě erytroferon a tomu se chci věnovat. Zaměřit se na největší efekt – to je také věc, kterou jsem se naučil ve fyzice. Mám granty na příští tři nebo čtyři roky, na tu dobu mám práce dost a dost.

Na živých systémech je fascinující jejich složitost a značná redundance. Jednotliví hráči jsou propojeni sítí zpětných vazeb, a když jedna z cest přestane fungovat, organismus si zpravidla poradí a využije alternativní cestu. — A tam, kde redundance chybí, přicházejí choroby. Medikům rád vyprávím příběh o kosmické lodi, která putuje vesmírem. Je to starý typ – ještě z doby, kdy lidé běžně kouřili v uzavřených prostorách. Na palubě je s lidmi tajně mimozemšťan, který se snaží přijít na to, co je pro fungování lodi důležité. Ukradne baterii, aby zjistil, jaké to bude mít důsledky. Ale na lodi je několik záložních baterií, takže se nic dramatického nestane. Pak ukradne popelník. Ten je jen jeden, takže najednou začnou všichni nervózně pobíhat a hledají ho. Mimozemšťan z toho usoudí, že baterie důležitá není, zato popelník ano.

Mají vaše poznatky už nějaký dopad v klinické praxi? — Léky připravené na bázi toho, co jsme se dozvěděli, jsou v různých fázích klinického testování. Ty testy mohou a nemusí být úspěšné. Ale důležitější je, že jsme se naučili, jak pacientům správě podávat železo. Donedávna jsme jim říkali, že musí brát dvě tablety třikrát denně. Bylo to hloupé a dnes už to víme. Když si dáte železo, hepcidin vystřelí vzhůru – opět analogie s cukrem a inzulinem. A když si vezmete další tabletu, tělo už železo neabsorbuje, protože feroportin je hepcidinem zablokován. Takže je potřeba počkat, až hepcidin klesne, a teprve potom si vzít další tabletu. Dnes proto tablety podáváme obden. Týká se to třeba mladých žen trpících ztrátami krve při menstruaci. Železo dráždí žaludek, nyní ho můžeme podávat způsobem, který je mnohem efektivnější a šetrnější.

Je to pro vás důležité – vidět, že vaše objevy pomáhají pacientům? — Dělá mi to samozřejmě radost, ale primární motivace to není. Jsem zvědavý člověk, to je hlavní. Jsem rád, když vím, jak věci fungují.

Jak často jezdíte do České republiky? — Každé dva tři roky. Mám tu kamarády, ale nepracuji zde. Jsem zamilovaný do Prahy.

Kdy jste přijel poprvé? — Až po roce 1989. Do té doby jsem jezdit nechtěl, protože jsem tu byl odsouzen na dva roky vězení. Když jsem přijel poprvé, byl to ohromující pocit. (Přechází do angličtiny.) Myslím, že tohle je také vědecký problém: člověk je jako housátko Konrada Lorenze, prostředí svého dětství má imprintované. Ať chceme, nebo ne, prostředí, v němž jsme vyrůstali, je nějakým způsobem hluboce v nás, je naší součástí.

Vracel jste se do města svého dětství, ale zároveň jste musel vidět, jak je Praha zanedbaná. — To byla, ale to víte, odjížděl jsem v roce 1966. Měl jsem ji rád už zanedbanou.

Poznámky

1) Oliver Rácz (1918–1997), slovenský básník, spisovatel, překladatel, pedagog a komunistický politik maďarského původu. V roce 1944 zachránil několik Židů před transportem, koncem války se sám musel skrývat. (Pohnutý příběh dominikána Mikuláše Jozefa Lexmanna, který pomohl pro změnu jemu, přesahuje únosný rozsah této redakční poznámky.) Válečné zážitky zachytil v románu s autobiografickými prvky Dozvedela som sa, že žiješ (slovensky 1966, orig. Megtudtam, hogy élsz, 1963). Hrdina románu Židům, jimž hrozí nebezpečí, říká: „Nie som prorokom, no jedno viem: Nemci vás neženú do tehelne preto, aby vás tam prinútili robiť tehly. Tehelňa bude pravdepodobne len sústrediskom. Máte príbuzných v Nemecku alebo na Slovensku? Kedy ste dostali naposledy od nich správu? Odkedy ich deportovali, ani raz... No vidíte. Po tehelni príde niečo také, odkiaľ už nemožno podať správu.“

2) Park C. H. et al.: J. Biol. Chem., 2001, DOI: 10.1074/jbc.M008922200.

3) Pigeon C. et al.: J. Biol. Chem., 2001, DOI: 10.1074/jbc.M008923200.

4) Nicolas G. et al.: PNAS, 2001, DOI: 10.1073/pnas.151179498, viz také Vesmír 81, 253, 2002/5.

6) Arezes J. et al.: Cell Host & Microbe, 2015 DOI: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.12.001.

7) Kautz L. et al.: Nature Genetics, 2014, DOI: 10.1038/ng.2996.

8) Coffey R. et al.: Blood, 2021, DOI: 10.1182/blood.2021014054.

English version (Translated from Czech by Tomas Ganz):

The Man with the Iron Love

"Would you mind if I spoke about iron in English? I am not used to thinking about it in Czech," says Tomas Ganz at the beginning of our meeting. He is the discoverer of key hormones regulating iron metabolism, and has been living and working in the United States for fifty-six years now. Although the biographical and personal parts of the interview were conducted in Czech, he also switched to English after a question about his relationship with Prague. Because that, too, is science... The story of his family is, among other things, a testimony to the turbulent history of Central Europe in the 20th century.

Your father, Vilem, was a successful cardiologist, later world-famous as William Ganz, so you were close to science since childhood. It would not have taken very much for everything to be dramatically different. — That is true. Dad was born in Košice, Czechoslovakia, and in 1937 he began studying medicine in Prague. But after the Munich agreement in September 1938, Czechoslovakia was split and carved up with the border regions ceded to Nazi Germany and its allies. Košice was transferred to Hungary, my father lost his Czech citizenship, was kicked out of the university and returned home. As a Jew, he found himself in a Hungarian labor camp. He faced mortal danger when the Germans occupied Košice in 1944 and began the transports to concentration camps.

What saved him? — Rather, who saved him. A Hungarian soldier approached him on the street and warned: "The Germans will kill you. Don't listen to what they tell you. Here is a ticket for the train to Budapest, it is safer there. My maid will take you to the train station." And so it happened. Dad didn't know the officer well or his reasons for risking his own execution, along with his entire family. More than fifty years later, I was at a congress in Milan and there I was approached by a man about my age: "My name is Oliver Rácz, I am a pathologist from Košice, and I am the son of the man who saved your father."

That's what I call a meeting! — It was incredible. He knew the whole story. His father, Oliver Rácz Sr., had already passed away by then, having died in 1997.

Did you learn why he helped your father then? Did he help other people? — He was by nature a dissident. He had leftist sympathies, in the sixties he was a member of the Slovak National Council and then of the House of Nations of the Federal Assembly (until 1971, ed.) but he was not dogmatic in any way. And during the war he had a Jewish girlfriend – later they got married. He helped her and her family first and then other people, my father was not the only one.9) So I think two factors played a role in this: love and idealism. Later, I helped get his name inscribed in the Yad Vashem Memorial.

So your father survived the war, what next? — In Budapest he met my mother, who was also in the underground. After the war they got married and my father returned to Prague to study medicine at Charles University. He graduated in 1947. I think he served as a doctor in the border region for a year, then he joined the hospital Na Bulovce, in internal medicine which was headed by Professor Klement Weber. In 1951 Prof. Weber became the director of the newly founded Institute for Circulatory Disorders in Prague-Krč. He knew my dad had talent, so he invited him there. My father was engaged in research at the institute, specializing in coronary circulation. He did truly cutting-edge science at the international level, published in world-class journals, there were not many such experts in our country at that time.

So you were born in Prague. — At the clinic on Roosevelt Street. Mom later said that the name of the street predestined my fate.

The fate of an emigrant to the United States? — The whole family left in 1966, when I was eighteen. I don't know how it happened but we all got passports and went on holiday to Austria and Italy. We did not return. My mom had a brother and sister in Los Angeles, so we joined them. Dad learned English, got a position at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center and continued the research he started in Krč.

And successfully. — Successfully, in coronary physiology he was very successful. He was not only a scientist, but also an inventor. He worked hands-on in the laboratory, and in the early seventies he and Jeremy Swan developed the so-called Swan-Ganz catheter for measuring blood flow and pressures in the pulmonary artery. This is the peculiarity and advantage of America. A person can arrive there, not speaking English well, not knowing the system, and yet he can succeed.

Your younger brother followed in his father's footsteps. — Yes, my brother Peter is a successful cardiologist at the University of California, San Francisco. He had the courage to do it, I wanted to do something else.

Even something completely different. It wasn't hematology right away, was it? — It wasn’t, I did physics. In Prague, I attended the high school on Štěpánská Street in the center if the city, I was one of the so-called cybermen. That was kind of an experimental program at the time, we had five physics classes and ten math classes every week. And also programming. I liked it, I planned to study mathematics and physics at the university. Then, when I started studying at the University of California, Los Angeles, they placed me straight into my second year because I was a year ahead of the American high school graduates. I then went to Caltech for my PhD, where I worked on experimental superconducting circuits. I was good at it, I was interested in it, so I didn't really care who was funding the research but it was the military. So when the Vietnam War ended, the type of research I was working on was among the first to lose funding. So I convinced myself that I had to try something else.

How does it happen that a physicist turns to medicine? — I was interested in biology, even though I had never studied it before. I had a professor who inspired me in this direction, Max Delbrück.

Did Max Delbrück teach you? — Yes, the 1969 Nobel Prize winner. He was a physicist who made his mark in biology and introduced me to it. He was interested in genetics and viruses, and I wanted to do what he did. That didn't quite work out, because I found out that I had to learn everything by myself. With one doctorate, it was impossible to pursue another – the only exception was medicine. So I went to study medicine because of biology. Not that I wasn't interested in patients, but I wanted to be primarily a scientist — like my dad and like the heroes I had read about in your magazine Vesmír (Universe) and later in The Scientific American.

What decided your next specialization? — I did not want to work on popular topics in which there is a lot of competition and huge pressure for results. I wanted to have time to think things through. So I wasn't attracted to cancer research and similar popular areas. I was looking for a field where there would be "silence and tranquility". I was fortunate to get into Robert Lehrer’s lab as a postdoc in 1983, and he introduced me to hematology. I found it terribly interesting – also because you can easily get material for research.

Josef Prchal told me the same thing: "Most people are quite willing to give blood samples. Doing a brain or heart biopsy is a lot more complicated." (Vesmír 100, 668, 2021/11) — That's right. You can immediately look at the blood under a microscope, it is still alive, the cells are moving... Fantastic!

But didn't you regret leaving physics? — Yes, a little, but sometimes the knowledge came in handy. For example, I knew how to repair laboratory instruments. It saved me thousands of dollars.

And was it just that practical advantage? After all, physicists think differently than biologists, Max Delbrück was not the only one who enriched biology with a physics approach. — You're right. Physics gave me two things: quantitative thinking and the ability to make estimates. Not just to ask what will happen, but how much will happen. If I use this instrument, will I measure or see what I need to measure or see? Is the device sensitive enough? Many biologists are not used to thinking like this.

Lehrer brought you to study antimicrobial peptides? — Yes, he was a pioneer in this field. We asked ourselves whether white blood cells make antibiotic substances that help the body fight bacterial infections. At the time, it was widely accepted that white blood cells kill pathogens by forming oxygen radicals but we knew patients who didn't form any oxygen radicals, and yet they didn't get infected. We asked if there were any other ways to destroy microbes. Our approach to studying this problem was very simple, but it worked: We collected billions of white blood cells from humans and animals, we extracted the cells, gave the extracts to the bacteria, and observed which extracts could kill them. So we discovered peptides with antimicrobial effects, which we named defensins. I studied them for ten years, and we found out that defensins are not only in white blood cells, but also in the skin, on mucous membranes, in urine... We found them practically everywhere.

And that's how you discovered hepcidin... — One day, a lab technician brought me a chromatogram. It was a human urine sample. I looked at the tracings and it was clear to me that there was something unknown there. That peak didn't react with our antibodies to defensins. We analyzed it and it was a new peptide. Like defensins, it was able to kill bacteria and we found that it came from the liver. That's why I named it hepcidin.10)

How did you come up with its role in iron regulation? — I put the new peptide into the database and then a colleague from France contacted me with the news they found the same peptide in mice that were given iron-rich food.11) They found that the livers of those mice produced large amounts of this peptide. A bell rang in my head: This is not going to be a run-of-the-mill defensin! One of the people who worked in that French lab then went to another lab where they studied a transgenic mouse missing the gene for USF2. When they opened the mouse, they found that the liver and pancreas were completely dark-colored from iron and, on the contrary, it had less iron in the spleen compared to the control. And they put it all together: The genes for hepcidin and for USF2 are right next to each other, and it turned out that the gene for hepcidin was also knocked out in this mouse.12) So it occurred to them that hepcidin might be the iron-regulating hormone that everyone was looking for. They asked us what we thought about it. Well, and I threw away everything I was working on at that time and began to fully devote myself to hepcidin. Thanks to mouse models and human patients, we gradually put it together: hepcidin is a hormone that regulates the amount of iron in the body.

Hepcidin regulates iron in the same way that insulin regulates sugar? — It's exactly the same thing. Both are peptide hormones, insulin lowers blood sugar, hepcidin lowers iron levels. But it is interesting that hepcidin is made in the liver. We're not used to thinking of the liver as an endocrine gland, but it is that. If hepcidin is not formed, either due to mutations in its regulators, or in the gene itself, a person becomes ill with hereditary hemochromatosis. A healthy person has 3 or 4 grams of iron in the body. People with non-functional hepcidin can have ten times this amount. Without treatment, the excess of iron then destroys everything in the body – liver, pancreas, heart muscle... If too much hepcidin is produced, a person becomes ill with iron deficiency anemia – there is not enough iron for the production of red blood cells.

Hepcidin binds to ferroportin – a transmembrane protein in enterocytes (cells forming the intestinal lining) of the duodenum, in macrophages and in some other types of cells. Ferroportin ensures the transport of iron from the cell to the blood. Hepcidin blocks ferroportin and causes its degradation. But if iron continues to come with food, what happens to it? Does it accumulate in enterocytes, or do they stop absorbing it from the intestine?

Both are happening. Iron accumulates in the enterocytes of the duodenum, which at some point stop absorbing it further. But the most important thing is that enterocytes live only two to three days. So the cell dies and we flush it down the toilet – together with its iron. Enterocytes are fascinating in themselves, you could fill an entire magazine with a story about them. Why does the body produce cells that have such short lives? The explanation may be the corrosive environment they face. Now that I am eating salad in a café, I might wonder how my body digests it, but the gut cells survive? The correct answer is that those cells don't live that long. They die early, which is why the body has to renew them so intensively.

What about the antimicrobial activity of hepcidin, because of which you first noticed it? — I think it is such an evolutionary curiosity. The function of hepcidin is not primarily antimicrobial, but carries with it its evolutionary origin – it probably belongs to the same group of peptides as defensins. But its role in the defense of the organism is still there. When animals or humans are infected, the level of hepcidin increases dramatically – as much as a thousand times. When I suffered from a urinary tract infection, I monitored the level of hepcidin on myself. It rose a thousandfold and then fell again. From my own urine I obtained several milligrams of hepcidin. It was such a rich resource! In English, we have a saying: if God gives you lemons, make lemonade. So I made hepcidin.

But why does hepcidin go up so much? — Iron is, among other things, food for bacteria. So, when humans or animals are infected, it makes sense to reduce the amount of available iron and starve the bacteria. For the organism, this is not suicidal behavior, since red blood cells live for four months. So if the body stops their production for a week or two, it does not matter at all. The organism calculates: now we need white blood cells, not red ones,13) and microbes need iron. Thus, we stop the production of red blood cells and reduce iron levels. Hepcidin coordinates the whole thing. We know this because we studied a transgenic mouse that doesn't have hepcidin. When you infect it with Gram-negative bacteria, it dies within twelve hours, while the control mice do not even get sick.14) It was a terrifying experiment. They called us from the animal facilities: "All your mice are dead! You can't keep doing it, it's against the rules."

The blood concentration of hepcidin tends to be high even in chronic inflammation, which can lead to anemia. But this could damage the body. So why does the level of hepcidin not fall? — We may ask whether such anemia is good for people suffering from chronic inflammation. My simple answer is: evolution doesn't care about chronic diseases. In the not so distant past, if you had a chronic illness, you died. If a person lived to be thirty or thirty-five years old, it was a full life. Thus, anemia can be a side effect of trying to protect the body from infection, it may not have any other function.

How widespread is hepcidin in the animal kingdom? — We find it in vertebrates. For the first time it appears in fish, and there it is interesting, because some of them have two types of hepcidin. One works as a hormone and the other possibly as an antimicrobial peptide. Again, we deal with the evolutionary origin of hepcidin. In the invertebrates, hepcidin is absent, although they have ferroportin. Ferroportin is also present in primitive multicellular animals such as hydra. Ferroportin was even found in some bacteria but they could have stolen it from animals.

So in invertebrates, is ferroportin regulated differently? — Yes, but we don't know how yet.

But your discoveries of iron-regulating hormones did not end with hepcidin. — Hepcidin was the first part of that scientific story. The second part was the question of how red blood cells are provided with sufficient iron. There must be some regulatory mechanism that allows red blood cell precursors to "ask for iron." So we were looking for another hormone and in 2014 we found it – and named it erythroferrone.15) A lot of work was done by my French postdoc Léon Kautz. Erythroferrone inhibits the production of hepcidin, so ferroportin can release more iron into the body. We are still working on ferroportin. We recently published a new article in the journal Blood reporting on a transgenic mouse that produces too much erythroferrone and therefore suffers from iron overload.16)

When I read about iron regulation, I came across the fact that a person can suffer from both iron overload and anemia. How does something like this happen? — Anemia can develop as a result of the treatment of hemochromatosis. Hemochromatosis is treated using a very ancient method that was used for many things, but in this case it really makes sense – commonly known as bloodletting. A milliliter of red blood cells contains a milligram of iron. So, if the patient has an excess of 10 grams of iron, you need to gradually take from them 10 liters of red blood cells, that is, from 20 to 30 liters of blood. During this process, you can cause anemia, because iron does not mobilize quickly enough.

And another possible cause? — There are diseases that combine anemia with what looks like hemochromatosis. An example is thalassemia. Here, red blood cell precursors produce too much erythroferrone. This is due to the fact that the precursors divide, produce erythroferrone but do not differentiate into red blood cells. Some patients have bone marrow in every bone – in the skull, in the fingers, which are swollen because of it. Bones are full of precursors that try in vain to form red blood cells.

Why are they failing? — For genetic reasons, the formation of one of the globin chains (alpha or beta) is damaged, so there is an imbalance, hemoglobin is not formed, excess globin precipitates in the cell and kills it. Erythropoietin reacts to the lack of red blood cells, the concentration of erythropoietin shoots up to stimulate the production of red cells but they cannot be produced. During that vicious circle, the precursors are still producing erythroferrone, which inhibits hepcidin production. So the whole system goes crazy.

Do you expect the discovery of other regulatory molecules? — It is possible that erythroferrone is not the only hormone with this function, we also see traces of something else, but I do not want to work on it. Most of the effect is accounted for by erythroferrone and I want to devote myself to that. Focusing on the biggest effect is also something I learned in physics. I have grants for the next three or four years, and for that time I have enough to do.

What is fascinating about living systems is their complexity and considerable redundancy. Individual players are connected by a network of feedbacks but when one of the paths stops working, the organism usually copes and uses an alternative path. — And where redundancy is absent, diseases develop. I like to tell the medical students the story of a spaceship. It's an old type – back in the time when people used to smoke in enclosed spaces. Along with humans on board, there secretly lives an alien trying to figure out what is important for the ship's operation. He steals a battery to see what the consequences will be. But there are several backup batteries on the ship, so nothing dramatic happens. Then he steals an ashtray. There is only one, so suddenly everyone starts running around nervously looking for it. The alien concludes that the battery is not important but the ashtray is.

Do your findings already have any impact in clinical practice? — Drugs based on what we have learned are in various stages of clinical trials. Those trials may or may not be successful. Perhaps more importantly, we are learning how to administer iron to patients. Until recently, doctors told them that they had to take two tablets three times a day. It was dumb and we now know why. When you take iron, hepcidin shoots up – again, analogous to sugar and insulin. And when you then take another tablet, the body no longer absorbs iron, because ferroportin is blocked by hepcidin. So, you need to wait until hepcidin comes down again, and only then take another tablet. Today, therefore, we give the tablets every other day. This applies, for example, to young women suffering from blood loss during menstruation. Iron irritates the stomach, now we can feed it in a way that is much more effective and gentle.

Is it important to you – to see that your discoveries help patients? — It makes me happy, of course, but it is not my primary motivation. I'm a curious person, that's the main thing. I like to know how things work.

How often do you go to the Czech Republic? — Every two or three years. I have friends here, but I don't work here. I am in love with Prague.

When did you first arrive? — Only after 1989. Until then, I didn't want to go because I was sentenced to two years in prison. When I first returned, it was an overwhelming feeling. (Transitions to English.) I think this is also a scientific problem: humans are like the goslings of Konrad Lorenz, the environment of his childhood is imprinted. Whether we like it or not, the environment in which we grow up is somehow deep within us, it is a part of us.

You were returning to the city of your childhood, but at the same time you had to see how neglected Prague was. — It was, but you know, I left in 1966. I loved her already neglected.

Footnotes

9) Oliver Rácz (1918–1997), Slovak poet, writer, translator, pedagogue and communist politician of Hungarian origin. In 1944 he saved several Jews from transport, at the end of the war he himself had to hide. (The moving story of the Dominican Nicholas Jozef Lexmann, who, for a change, helped Rácz, exceeds the scope of this editorial note.) Rácz captured his war experiences in a novel with autobiographical elements Dozvedela som sa, že žiješ (Slovak: 1966, orig. Hungarian: Megtudtam, hogy élsz, 1963, translation: I found out that you are alive). The hero of the novel tells the Jews, who are in danger: "I am not a prophet but this I know: The Germans do not force you to gather in the brick factory to make bricks. The brick factory is just a collection point. Do you have relatives in Germany or Slovakia? When did you last hear from them? Since they were deported, not even once... Well, you see. After the brick factory comes a place from where it is not possible to send news."

10) Park C. H. et al.: J. Biol. Chem., 2001, DOI: 10.1074/jbc. M008922200

11) Pigeon C. et al.: J. Biol. Chem., 2001, DOI: 10.1074/jbc. M008923200

12) Nicolas G. et al.: PNAS, 2021, DOI: 10.1073/pnas.151179498, see also Vesmír 81, 253, 2002/5

13) See p. 82 of this issue (in Czech).

14) Arezes J. et al.: Cell Host & Microbe, DOI: 2015, 10.1016/j.chom.2014.12.001

15) Kautz L. et al.: Nature Genetics, 2014, DOI: 10.1038/ng.2996

16) Coffey R. et al.: Blood, 2021, DOI: 10.1182/blood.2021014054

Ke stažení

článek ve formátu pdf [323,45 kB]

článek ve formátu pdf [323,45 kB]

O autorovi

Ondřej Vrtiška